Allen Christian Redwood and the 55th Virginia Regiment

1863: The Tide Turns

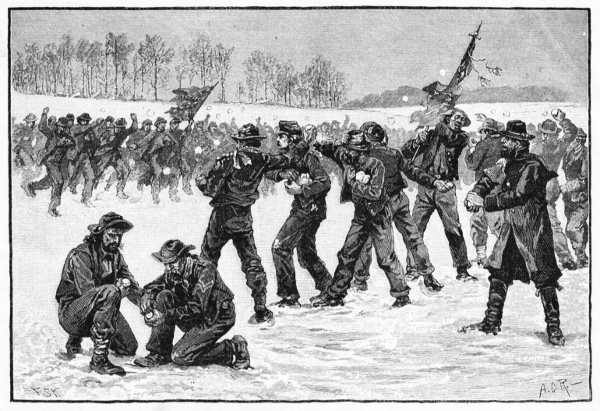

Four days after the repulse of the enemy at Fredericksburg, Jackson's Corps marched to Moss Neck, where it became snowed in. The Light Division named its new quarters: ‘Camp Gregg’. It would be the 55th's home for the next four months (Image 1):

Despite describing this interval as “dreary [and] mud-bound”, Redwood conjured up some fond memories of it, recalling frequent snowball fights, occasional games of base-ball (known as ‘chermany’), amateur theatricals and even some surreptitious gambling.1 He also recalled some further exploits of the 55th's camp servants.

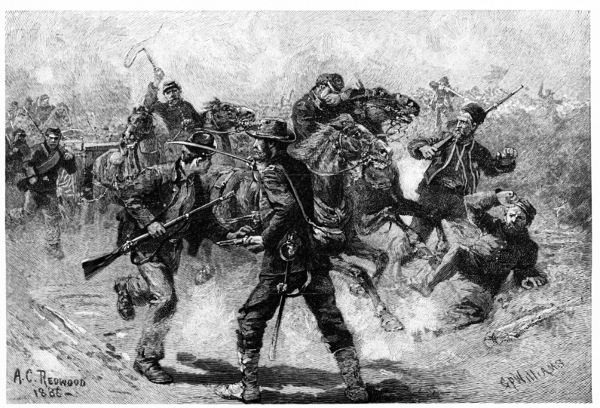

Image 2 shows the snowball fight that Redwood chose to portray was one involving “whole brigades, arrayed in line and with colors flying.”:

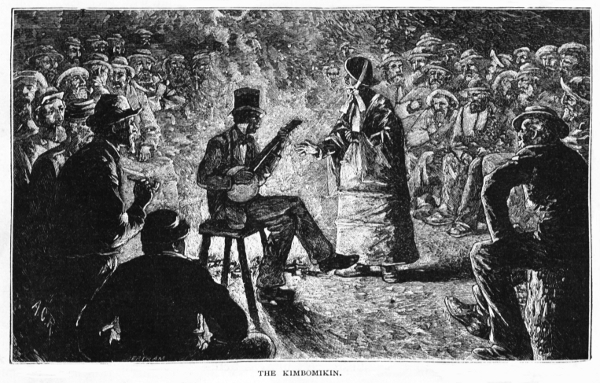

His depiction of the amateur theatricals provides another invaluable window into the social life of the Confederate Army. The performances were held in an area known as ‘The Kimbomikin’:

“The Kimbomikin was a circular pen, hedged all round with pine brush, sloped inward, as a winter shelter for cattle is usually constructed in the South. A “lightwood” fire in the center did duty as a general illuminator, and in the arena surrounding this was the stage, the audience finding what accommodation they could about its circumference. Naturally there was no dressing-room for the performers, who vanished into the outer darkness whenever any change of attire became necessary – the “assistance” being kept in good humor meanwhile by a vocal solo with banjo accompaniment, or a little “light clog business.” ”

“With a little indulgence from the house, the difficulty of compassing feminine attire was triumphantly solved. A number of barrel-hoops, strung together, made a sufficiently proper crinoline, which was draped with a shelter-tent and an army blanket, supported at the waist by a cartridge belt, and doing duty as petticoat and overskirt respectively; while a wide brimmed slouch hat, tied on by a band passing over the crown, was the approved thing in bonnets… ”

The entertainment consisted mainly of stand up comedians doing Irish and Negro impressions, with a good deal of ad-libbing and heckling coming from the audience. During sing-songs, the audience would join in enthusiastically at the choruses. “Refreshments were quite in order; a perpetual incense of pipe-smoke went up from the outer circle, while apples, ginger cakes and “goobers” met with ready demand… ” (Image 3):

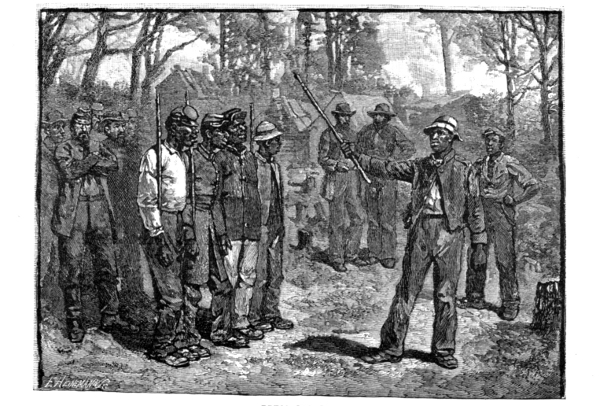

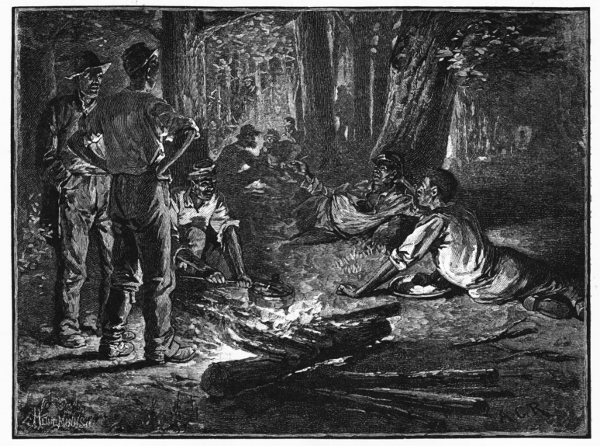

Fed up with being mistaken for a soldier by the provost and having his horses confiscated by the Q.M.D., Bill Doin's eventually left the regiment and went to work for the Commissary Dept., but Redwood was pleased to recall another of the 55th's camp servants, who served Co. C's Mess No.5 throughout the war and who was an equally fascinating character. His nickname was ‘Gin'ral Boeygyard’. Redwood provides us with no fewer than three portraits of this man. Neither a great cook, nor overly concerned with hygiene, Boeygyard was another accomplished and daring forager – not to mention purloiner of firewood. He exercised complete authority over the company's cook boys, whom he occasionally took for drill practice (Image 4). His greatest triumphs were yet to come:

Redwood's recollections give an insight into one side of life at Camp Gregg (Image 5). In a letter to his brother dated February 21st 1863, Pvt. Boswell Brizendine of Co. A, 55th Va. provides us with a stark view of another side:

“I… have been thru more then I ever did in my life. I went out to work on the road and we had to cut poles [trees] and toat them about a half mile and pole [corduroy] the road. We went out… Saturday and stayed out there until Friday and was about six miles from camp, it snowed and rained all the time, the snow was about 16 inches deep, and no where to sleep but out in the snow and rain and we had nothing to eat but bread and no salt in that. It was brought out only once a day.” He continued, “Well brother I will tell you all about the court martial... Today I am on guard and brother I saw something just now I never saw before. I saw two white men hit thirty nine licks a piece and I was one of the guards… and had to stand by and see it done... It was cold and they had to take off their shirts and had their skin cut and were tied to a hickory tree before the whole Brigade and were whipped... Brother, Musco Dunn was sent to Richmond to be put in Castle Godwin with a ball and chain to his right leg weighing 12 pounds to stay there 5 months at hard labor. George Durham was sent there to stay six months at hard labor with a ball and chain to his leg. John Harmon was sent there also to stay six months at hard labor and wear a ball and chain and then sent out of Virginia to the south and put in the army out there to stay until the war is over, and a great many are sent to share the same fate...”2

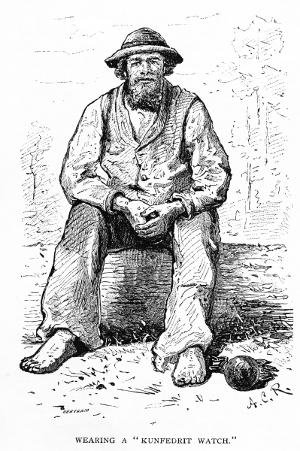

Redwood did not ignore this occurrence; indeed he recorded it in the accompanying heartfelt pictures, but characteristically he skirts round it. Admitting Johnny could sometimes be ‘naughty’ and guilty of ‘running the block[ade]’, he simply chooses to remember a joke made by one of those sentenced to wear a ball and chain – apparently it was a ‘Kunfedrit watch’ (Image 6). Yet, as Brizendine makes clear, the punishments were exceptional and, as the men's service records show, meted out for the serious offence of desertion. Of the twenty-three members of the regiment sentenced to incarceration in Castle Godwin six were dead from small pox and typhoid within weeks.3

In January 1863, Redwood's kinsman, William S. Christian, returned to duty having recovered from a wound received at Frayser's Farm. Christian was now Lt. Col. of the 55th and seems to have wasted little time in securing Redwood's appointment as Regimental Sergeant Major. Promotion to a position of such responsibility must have been a daunting prospect for an eighteen-year-old more used to observing events than dictating them, but Redwood stuck with it for over two months before finally resigning and returning to the ranks of Co. C, on April 15th 1863.4

Active campaigning resumed two weeks later and, near Chancellorsville, on the morning of May 2nd Redwood was privileged to witness the last meeting of the army's two greatest commanders:

“Before we reached the plank road, in a small opening among the pines were two mounted figures whom we recognized as Lee and Jackson. The former was seemingly giving some final instructions, emphasizing with the forefinger of his gauntleted right hand in the palm of the left what he was saying – inaudible to us. The other, wearing a long rubber coat over his uniform (it had been raining a little, late in the night), was nodding vivaciously all the while.”5

Lee’s instructions were for a crushing attack on the enemy's 11th Corps, which Jackson implemented later that evening after a twelve-mile flank march. The Federal troops were sent reeling in panic down the Orange Plank Road. In recording these events, Redwood introduced a new aspect to the telling of his wartime experiences. Instead of showing his regiment in action, he portrays the effects of its deeds on the enemy (Image 7):

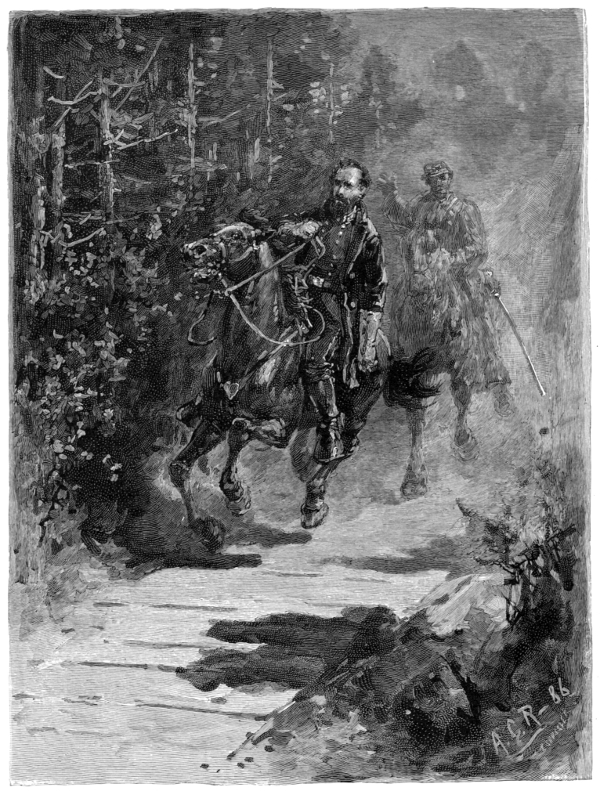

Eventually, as darkness fell, Jackson's attack stalled. The 55th was moved forward from reserve in order to renew the assault. It filed through the front line, passed down the Plank Road and halted in an exposed position facing south with the enemy on its left flank to the east. Jackson in the meantime rode down the Old Mountain Road with his own staff and that of A. P. Hill to reconnoitre the enemy's position. Having located them, he turned back, passing to the rear of the 55th. Several of its men, mistaking his party for enemy cavalry, opened fire and this was followed by a volley from the 18th N.C. that brought down several men and mortally wounded Jackson. Jackson was hit in the right hand and twice in the left arm. Redwood can hardly have been much more than a hundred yards away when this happened. He later recorded the incident (Image 8). As in his portrayal of the death of Kearny, he shows the moment the bullets hit home. The general's left arm hangs limp and useless, his hat has fallen off and he is struggling to remain in the saddle.

As the stricken general was being carried to the rear by members of the 55th, the enemy opened a devastating artillery barrage enfilading the road and causing serious casualties. Colonel Mallory was killed and Redwood was amongst the injured, being stunned by a shell fragment.6 He may have recovered quickly from this concussion as he later wrote a detailed description of Jeb Stuart's arrival to take temporary command of the 2nd Corps [Jackson's] the next morning. It has the hallmark of an eyewitness account. If so, Redwood may have been involved in the heavy fighting of that day, in which the 55th was badly mishandled and suffered further serious casualties. Either way, he was fully fit by the commencement of the ill-fated Gettysburg campaign.

His coverage of that campaign falls into two parts. The first part is light hearted and ends with success in the first day's fighting; the second dwells on the horrors of the retreat. The watershed being the great charge on the third day; after which, the grimness of war is portrayed unrelentingly. Indeed, July 3rd 1863 is a watershed for the artist's treatment of the war as a whole.

Before invading Pennsylvania, General Lee issued strict orders that private property should be respected, but the men in the ranks did not regard this as applying to foodstuffs and happily ‘requisitioned’ whatever they needed. For Gin'ral Boeygyard it was a golden era. His tales of how he conned credulous ‘Dutch’ housewives out of provisions for his mess still amuse a century and a half later. Redwood paid tribute to his achievements with this picture of the camp servants of Co. C preparing food for their masters. Boeygyard is leaning back against a tree, pipe in hand, having already completed his work and is good-naturedly chiding those of his colleagues who have shown less enterprise in their foraging (Image 9):

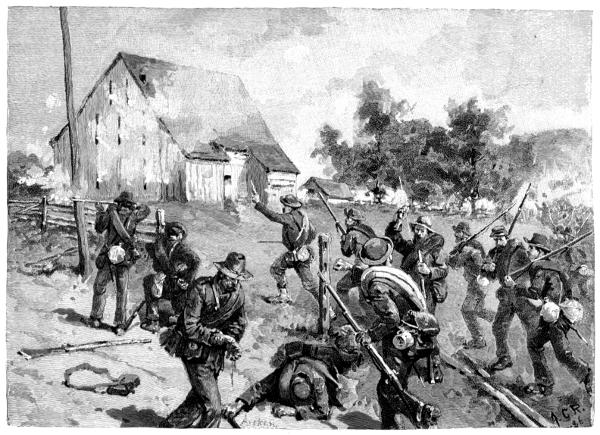

Throughout the month of June the advance proved deceptively easy and as the 55th Va. headed down the Cashtown Road towards Gettysburg on the morning of July 1st Redwood recalled no one was expecting trouble, but it came to them nonetheless.7 The resulting engagement exercised a special fascination for him. The field of action was dominated by a large stone barn that still stands today. The 55th Va. was given the task of storming it and the artist made two records of the resulting fight. The first, a charming watercolour, depicts the opening of the engagement. The regiment has just crossed a small stream called Willoughby Run and is pushing the enemy's skirmishers back towards the McPherson's Farm, to which the barn belonged (Image 10):

The second (Image 118) shows one of three full scale assaults made on the barn itself. The place was a natural fortress, but it was finally surrounded and its defenders forced to surrender when the troops either side of it were driven back. The 55th captured scores of prisoners and two battle flags.

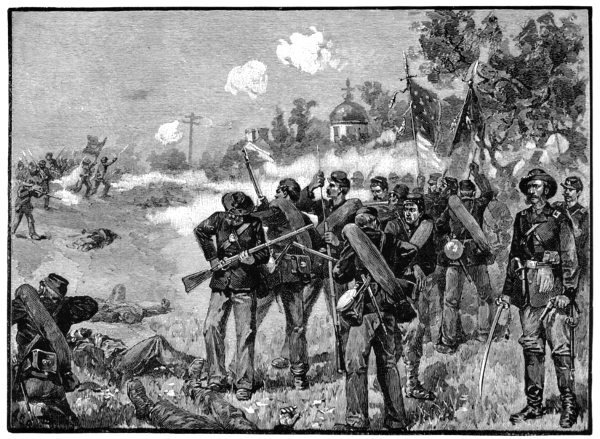

As he had when covering the battle of Chancellorsville, Redwood also took the opportunity to show the action from the enemy's point of view (Image 12). In this picture, the Federals have fallen back from McPherson's Ridge to Seminary Ridge, where, rather ominously, they are continuing to put up fierce resistance. The Seminary cupola is visible in the distance. The 55th came to a halt in front of this position. Out of ammunition and encumbered with prisoners, it wisely forbore from pressing the assault.

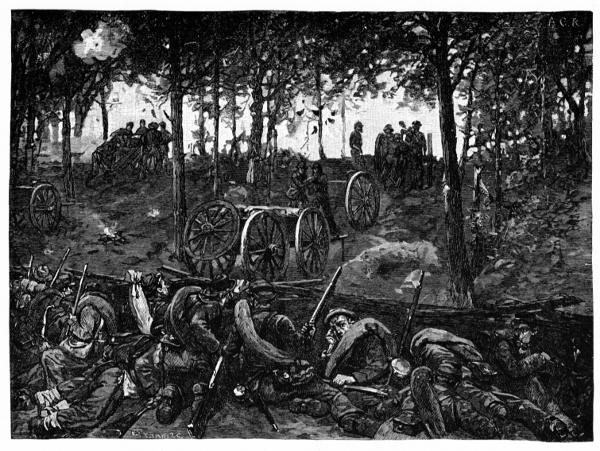

Two days later, the regiment was selected to take part in a major attack on the enemy's centre. It was in no condition to make the attempt. Of the 480 men carried into action at Chancellorsville two months earlier, only 230 were still present for duty (45 had been killed, 106 wounded and 15 captured. Thirty-five had deserted and the remainder had been left behind, or dropped out, sick). Over 50 of the casualties had been inflicted within the previous forty-eight hours.9 In preparation for the attack, the 55th's division was put back in line on the evening of the 2nd, bivouacking in Spangler's Wood on the reverse slope of Seminary Ridge – now in Confederate hands. At dawn on the 3rd, the troops awoke to find themselves positioned behind a long line of artillery. Redwood and his colleagues took one look at it and rapidly threw up a “slight barricade of fence rails, stones and turf.” The precaution proved a wise one as a brief, but intense artillery duel broke out soon after between some of these guns and the enemy's batteries on Cemetery Ridge. In Image 13, Redwood records the scene with his customary precision. A spherical case shot can be seen exploding at the top-left of the picture, causing a “spatter of bullets [to] rattle down among the caissons.”

Not long after, the enemy scored a direct hit on a caisson located directly in front of where Redwood was sheltering. It blew up and set fire to another nearby. At this critical moment a gunner appeared and calmly and systematically extinguished the flames. As the man turned to acknowledge the cheers of the infantry, Redwood recognized him — it was Jack…

That afternoon, following a two-hour artillery bombardment, the infantry moved forward to conduct their doomed assault.10 As soon as the men of the 55th emerged from the woods they could see they were being asked to do the impossible. They were on the extreme left of the line, with their flank in the air and no one in support. The regiment moved reluctantly forward until it reached a dip in the ground about five-hundred yards in front of the enemy line. Here most of its men refused to go any further. Duty bound, William Christian (now a full colonel and in command of the regiment) pressed on with the color-bearer and a handful of men. Redwood was one of those who loyally accompanied his relative. Just beyond a burning barn they ran into the 8th Ohio regiment, which poured a volley into them, wounding the color-bearer and several other men, including Redwood, who was shot in the right elbow while in the act of firing.11 Without waiting for orders, the party turned and fled.12

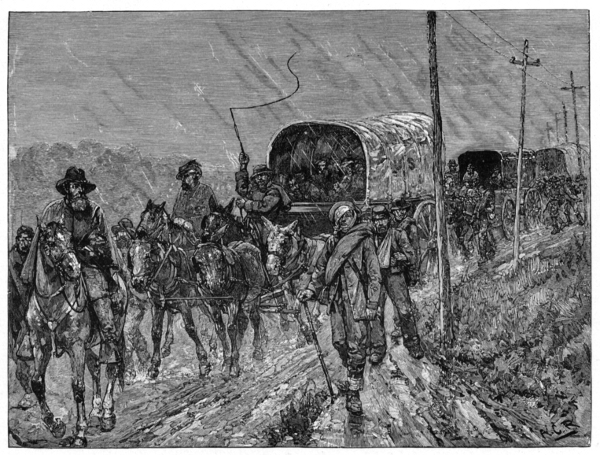

In the aftermath of the battle, Redwood was sent to join the seventeen-mile-long wounded train, which struggled homewards through appalling conditions. Its commander recalled:

“The rain fell in blinding sheets…. Canvass was no protection against its fury and the wounded men lying [in the wagons] were drenched… Scarcely one in a hundred had received adequate medical aid and… many… had been without food for thirty-six hours. Their torn and bloody clothing, matted and hardened, was rasping [against their]... still oozing wounds. Very few of the wagons had even a layer of straw in them and all were without springs. The roads were rough and rocky… The jolting was enough to have killed even strong men if long exposed to it.” Some men prayed, some swore fearfully in their despair and agony; others begged to be killed or taken out and left to die by the roadside. The majority stoically “endured without complaint unspeakable tortures… No help could be rendered… During this one night I realized more of the horrors of war than I had in all the two preceding years.”13

The journey must have been seared into Redwood's consciousness and his portrayal of it is a distillation of suffering (Image 14):

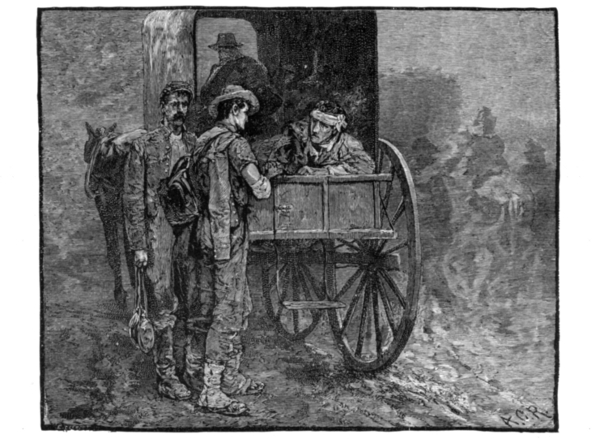

At Greencastle, Pa., while he was resting in the porch of a house, an ambulance drew up in search of water. Redwood recognised the driver as one of the gunners he had dined with a year earlier. In the ambulance was Jack, mortally wounded by a ball from a spherical case shot to the brain. It had paralyzed his tongue and he was unable to speak. Redwood's written account of his parting from his dying friend is a moving one, as is his visual record below (Image 15):

Redwood succeeded in getting back to Virginia. (Image 16).

He was granted a furlough from the Alabama Hospital in Richmond on July 29th and went to stay with relatives in Warrenton, N.C., returning to duty from there two months later, and drawing his back pay while passing through the capital on October 8th.14 He may or may not have been able to rejoin the regiment in time for the Bristoe Station campaign, but certainly participated in the subsequent Mine Run operation, during which the 55th was involved in fierce fighting on November 26th. Over half a century later he recalled his comrades at that time as, “… gaunt, shaggy haired men… with tattered blankets worn shawl-fashion in default of overcoats…”15

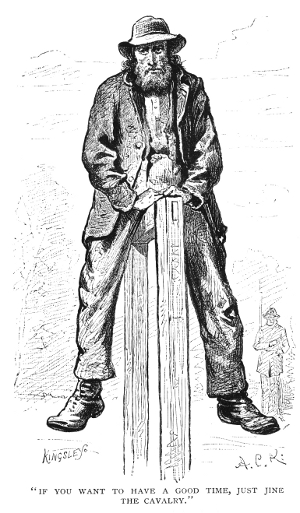

During the winter of 1863/64, the 55th was subjected to more than its fair share of hardship. On December 14th 1863, having just completed construction of its winter quarters, it was ordered to abandon them and proceed by railroad to the Valley of Virginia. There, in the bitter cold, without baggage or wagons, it spent weeks in a futile attempt to track down enemy cavalry, on one occasion marching twenty-eight miles in a single day. This must have forcefully impressed upon Redwood the benefits of belonging to the mounted arm.

Life in the 55th was beginning to pall. Colonel Christian and some of the regiment's best men had been captured in a rearguard action during the retreat from Gettysburg and were now prisoners of war. Another cousin, Lt. Allen Christian had left Co. C in November upon being appointed Asst. Surgeon of the 44th Georgia Regiment. Like many young men who had spent the previous two-and-a-half-years in the infantry, Redwood began to hanker after the more exciting and less restrictive life of a cavalryman. For most, this was a pipe dream, but Redwood had two trump cards; firstly he had relatives who could supply him with a horse; and secondly he was from Maryland. Marylanders serving in Virginian regiments could ask to be reassigned to units from their home state. Redwood played both cards and on January 12th 1864 he obtained a transfer to Co. C, 1st Maryland Cavalry Battalion, stationed at Hanover Junction.16

Notes

1 Redwood refers specifically to the following games: seven-up, old ledge and chuck-a-luck.

2 Letter courtesy of Mr. Glenn Samples.

3 Statistics collated by the author from the Compiled Service Records of the 1,324 soldiers of the 55th Va..

4 Redwood's Compiled Service Record, U.S. National Archives, M-324, roll 968.

5 Miller's Photographic History, Vol. 10, page 114.

6 Confederate Veteran, Vol. XXXI 1923, page 67

https://archive.org/stream/confederateveter31conf#page/66/mode/2up

7 Miller's Photographic History, Vol. 8, page 166.

8 The picture's full title is “Assault of Brockenbrough's Confederate brigade (Heth's Division) upon the Stone Barn of the McPherson Farm”.

9 Statistics collated by the author from the Compiled Service Records of the 1,324 soldiers of the 55th Va..

10 The men of Heth's division, to which the 55th and its brigade now belonged, avoided referring to the attack as “Pickett's Charge”. In a letter written in the 1880s, Robert Healy thanked Redwood for illustrating the 55th's part in the battle. “… I envy no one, but … I would like to have my brigade mentioned. You know our brigade was there... and now it is Pickett this & Pickett that. I am tired of it all...”

11 Confederate Veteran, Vol. XXXI 1923, page 67

https://archive.org/stream/confederateveter31conf#page/66/mode/2up

12 Reminiscences of a Rebel, by W. F. Dunaway, page 93.

13 Battles and Leaders, Vol. 3, pages 423-424.

14 Redwood's Compiled Service Record, U.S. National Archives, M-324, roll 968.

15 Confederate Veteran, November 1922, Vol. XXX, page 425.

16 Redwood's Compiled Service Record, U.S. National Archives, M-324, roll 968.