Allen Christian Redwood and the 55th Virginia Regiment

1862: The Year of Victory

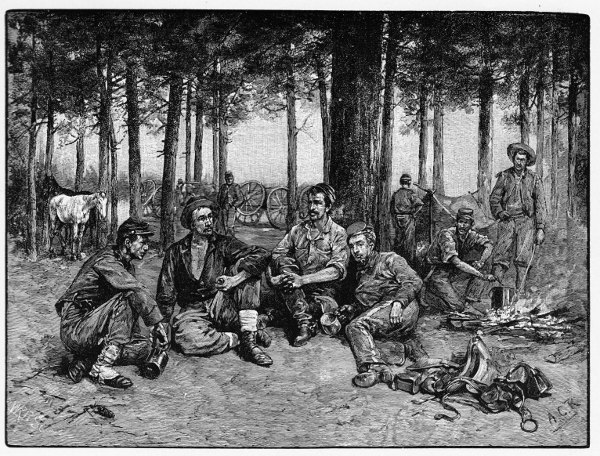

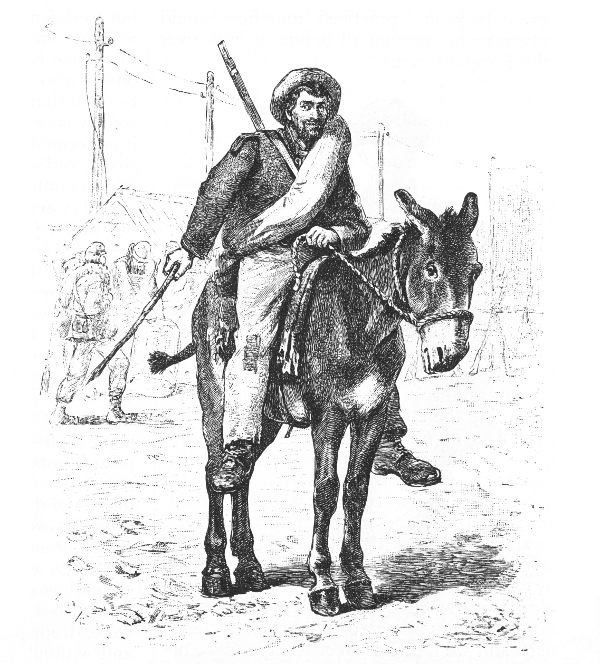

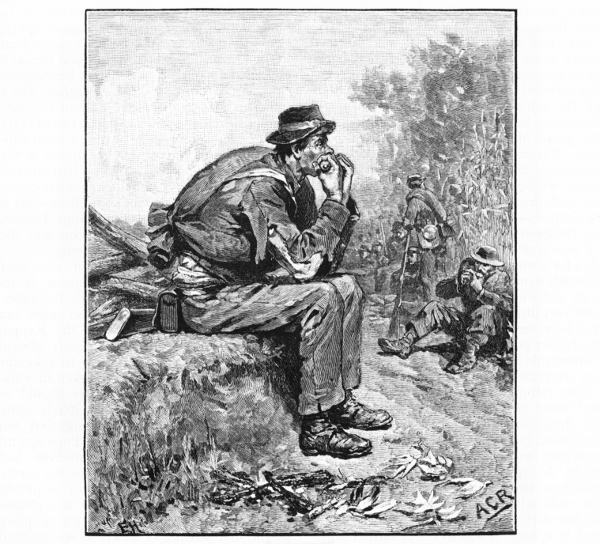

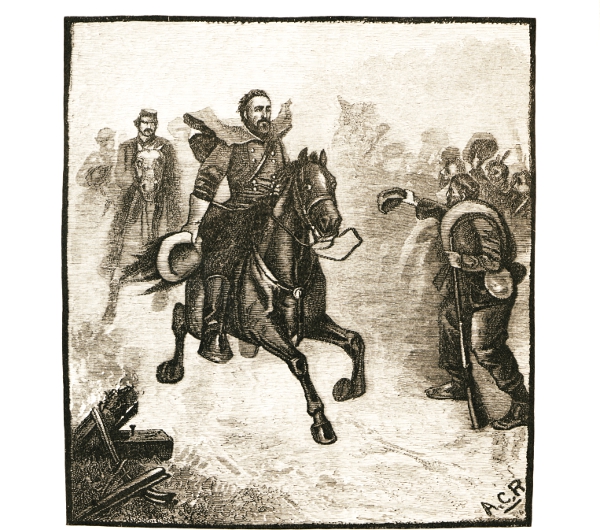

In the late spring of 1862, the 55th was assigned to Field's Brigade of A. P. Hill's Light Division and sent to help defend the capital, Richmond. Redwood received a slight contusion wound at Mechanicsville on June 26th 1862 and was out of action for the remainder of the Seven Days' Battle.1 Despite this, he later produced a fine picture of the 55th's greatest triumph – the capture of Cooper's Battery at Frayser's Farm on June 30th (Redwood mistakenly identified the battery as Randol's). According to Federal general George A. McCall, who witnessed the attack, it was made “in V-shape, without order and in perfect recklessness.” Redwood felt the formation “was in no wise intentional, the apex of the V in question being simply the brigade commander, General Field, who personally conducted the attack upon the battery and the slope of the sides, as the prowess of his followers might determine.”2 The moment is faithfully reproduced in the picture (Image 1). Field is the officer with his hat on his sword. Ever precise with detail, Redwood even shows the enlisted men wearing newly issued Richmond Depot shell jackets with trim on cuffs, collars and epaulettes – though it is also worth noting that the jackets are somewhat tight at the elbow, a tailoring feature more akin to the 1880s than the 1860s. The central star of the battleflag bears the inscription ‘55 Va’.

Redwood's initiation to combat on the 26th had not been pleasant, “…for the first time, I saw a man killed in battle… A shell ploughed the elevation in front … and as I ducked I glanced back… and witnessed its effect... The body of a stalwart young fellow suddenly disappeared, and on the ground where he had stood was a confused mass of quivering limbs which presently lay still... Another took effect soon after… knocking over several men and killing one of them. By this time the fire had grown quite brisk…”3 Reading this and comparing it with the picture above, one discovers a dichotomy in the way Redwood expresses himself. While prepared to face up to the grim, even disgusting consequences of artillery and rifle fire when writing about it, he is careful to avoid referring to it visually. In his pictures injured soldiers suffer from only the most decorous of wounds, his dead are always whole. The dismembered bodies and the gore that surely haunted his thoughts never invade his canvass.

It would be easy to underestimate the teenager peering gormlessly out at us from his only wartime photo, but this is a man who will stay the course, see terrible things yet remain cheerful and resolute to the last; a man who will play a significant roll in formulating the image of the Confederate fighting man. His reaction to the heavy casualties suffered by his regiment in the battle for Richmond hints at his steelier side, “Dead comrades were buried out of sight, and so gradually they passed out of mind; the more seriously wounded were at home on leave, more to be envied than pitied, while the slightly wounded were returning to duty… none the worse for their scratches.”4

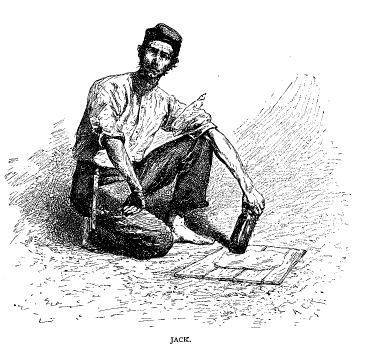

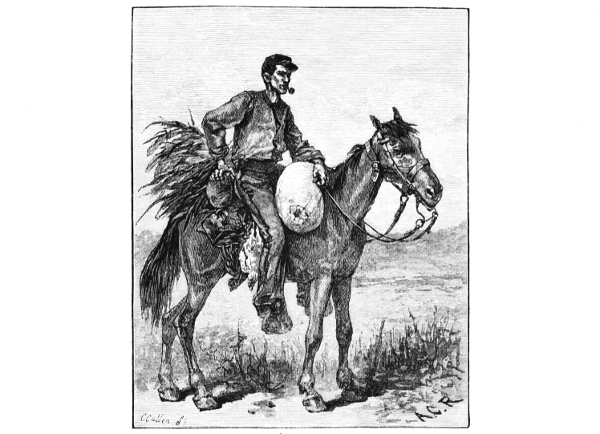

The month that followed stuck in his memory more as a period of calm than of sorrowful reflection. As the army recuperated, its soldiers visited neighboring camps, swapped stories and entertained one another (Image 2):

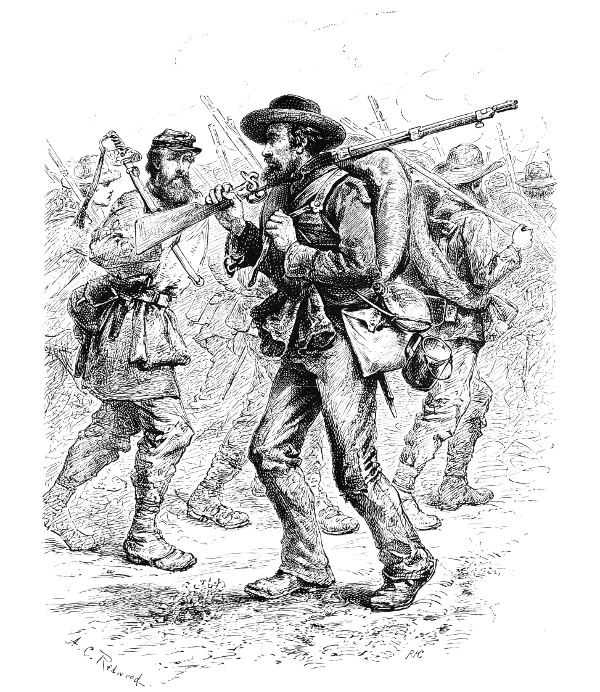

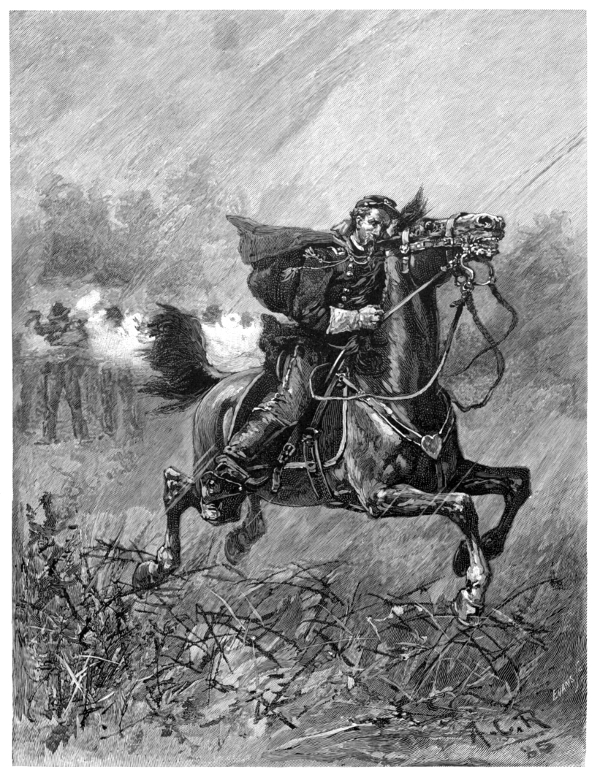

It was during one of these visits that Redwood met a young man who would make an enduring impression on him – a gunner named Jack (Image 3). Although the artist only spoke to Jack twice, for a few hours at most, and saw him briefly on one other occasion, he included him in three pictures and wrote an article about him for Scribner's Monthly in 1881.5 The detailed physical description of the gunner in the article coupled with the intimate nature of the picture entitled ‘A Camp Toilet’ (Image 4) might strike the modern reader as almost homo-erotic, but apparently caused no comment when viewed by veterans who had spent years in each other's company in the 1860s.

Redwood was not just fascinated by his new friend; he was also much taken with the idea of transferring to the artillery, but Jack managed to talk him out of it. The two young men would meet again, briefly, during the retreat from Gettysburg under much sadder circumstances.

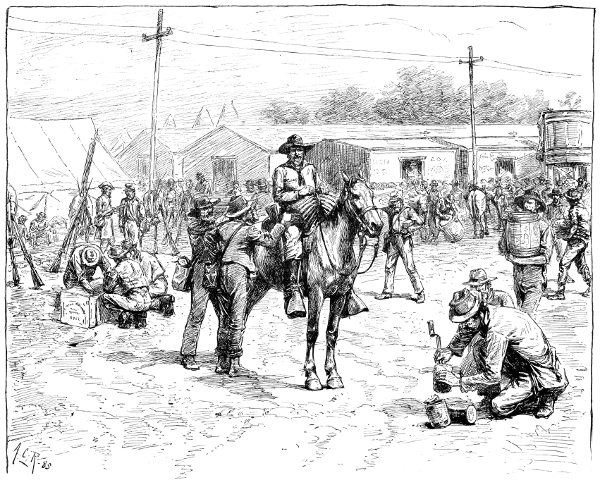

‘The Dinner Party’ was not Redwood's only depiction of camp life in the aftermath of the Seven Days' Battle. He also produced, ‘The Sinews of War’, the title of which is a slightly ponderous pun inspired by the stringy quality of the meat they were being issued (Image 5):

With the renewal of operations came hard marching and much suffering. The Light Division, to which the 55th belonged, was now attached to Stonewall Jackson's corps and that implacable commander would make the division earn its name. Redwood paid tribute to the exertions of his comrades in three pictures: ‘Route Step’ , ‘Passing the Rubicon’ and ‘Our March against Pope’.

‘Route Step’ (Image 6) shows a member of Jackson's Corps marching at the standard pace employed by Civil War armies on campaign 6.

‘Passing the Rubicon’ (Image 7) marks the opening of the all-out offensive designed to drive the enemy from northern Virginia. Its depicts troops removing their shoes, sock, trousers and drawers prior to crossing the Rapidan river in order to prevent chaffing from wet clothing and damage to footwear. The title is, of course, another Redwood pun.

‘Our March against Pope’ encapsulates the grim determination displayed by Jackson's troops at the start of their three-day, sixty-two mile dash for Pope's supply base at Manassas. Redwood amplified the point in writing, “The hot August sun rose, clouds of choking dust enveloped the hurrying column, but on and on the march was pressed without relenting. Knapsacks had been left behind in the wagons and haversacks were empty by noon; for the unsalted beef spoiled and was thrown away and the column subsisted itself… upon green corn and apples.”7 Once again the artist's attention to detail is impressive – the men are wearing knapsacks in the picture of them crossing the Rapidan, but not in this one (Image 8)8:

One thing that becomes apparent when viewing Redwood's work as a whole is his all-encompassing eye. He sees not just the battles, but also the long marches, periods of calm, amateur theatricals, punishments inflicted and jokes shared. He pictures not just men with muskets, but also camp servants, wagon drivers and even the enemy. All were there and all are remembered. In Image 9 he reminds us that not all the men he served with were heroes and introduces us to stragglers, “men, who wearing the garb of soldiers, yet never fight, – limping rearward with abstract gaze, as if they took no heed of the jeers that greet them at every step.”9

During the advance on Manassas Redwood broke down suffering from fever, probably contracted in the Chickahominy Swamp, and was ordered by Colonel Mallory to ride in one of the regimental ambulances. He was sufficiently fit to participate in the looting of the enemy's supply base at Manassas Junction on August 27th, 1862, recalling “For a change of underclothing and a pot of French mustard I owe grateful thanks to the major of the of the 12th Pennsylvania Cavalry… Whiskey was, of course, at a premium, but a keg of lager went begging in our company.” He has left us this glimpse of the joyous occasion (Image 1010):

Image 11 once again illustrates Redwood's attention to detail: the cans are of the ‘hole and cap’ type in use in the 1860s.

On reflection, Redwood decided against purloining one of the many captured horses and mules concluding it would only be a matter of time before some quartermaster took it from him, but he has left us this amusing picture of a comrade who took the risk (Image 12):

Having stirred up a hornet's nest, Jackson's troops escaped from the junction and took up a position along an unfinished railroad track. On August 29th, feeling somewhat recovered, Redwood picked up an Enfield rifle-musket and set out to rejoin his regiment. Unfortunately, he left his sick pass in the ambulance and was collared by a “courteous but firm” major of a Louisiana battalion, who “listened to my story with more attention than I could have expected, but attached my person all the same. “Better stay with us my boy, and if you do your duty I’ll make it right with your company officers.” ” Redwood was alternately fascinated and repulsed by the Louisianans with their myriad of accents, including ‘local gumbo,’ habitual gambling and cigarette smoking – the latter items “rolled with great dexterity between hands [of cards]”.11 When, inevitably, he came to leave us a portrait of this officer, he was careful to show him smoking a cigarette (Image 13):

That evening Redwood slipped away and again tried to find his own regiment. This time, with the arrogance of youth, he ignored a picket's advice “not to go down there” and ended up in the hands of the enemy. Although paroled and returned to the Confederacy within ten days of his capture, he was not exchanged until September 21st and did not rejoin the 55th until after the conclusion of the Sharpsburg Campaign.12 However, he was deeply interested in the fate of his unit during the time he was absent from it. He questioned his officers and friends closely as to what happened at Manassas on August 30th, at Ox Hill on September 1st and in Maryland and produced no fewer than seven pictures of these events. Two officers in particular provided important information. The first was Lt. Robert Healy of Co. C, a “gallant officer… whose rank was no measure of his service or merit”.13 In a letter dated April 17th 1885, Healy gave a detailed account of the fighting on August 30th and accompanied it with a useful sketch map. (Redwood later drew the accompanying portrait – Image 14) – on the envelope bearing Healy’s letter; it may well be a portrait of the lieutenant.14

This information provided the basis for Redwood's second splendid set piece battle scene that appeared in Century Magazine in 1886. The 55th Va. is shown rushing to the aid of troops in the unfinished railroad cut who have run out of ammunition and are defending themselves by throwing stones and handfuls of chippings at the enemy. The gap between the two groups of Confederates is the track-bed of the unfinished cut. The officer urging the men forward in Image 15 may be Colonel Frank Mallory 15.16

After his capture Redwood was taken to the headquarters of General Phil. Kearny, regarded as the bravest man in the Union Army, and was given a blanket by an orderly. The next morning he witnessed the general ride out, “a spare, erect, military figure looking every inch the soldier he was.” 17 Just two days later Kearny was killed at Ox Hill in circumstances outlined by the second of Redwood's informants, Captain James A. Haynes of Co. K, 55th Va.. Haynes recalled Kearny rode accidentally into the 55th's picket line during a blinding rainstorm, realised his mistake and bending low over his saddle, attempted to escape.18 The bullet that killed him entered his backside without leaving a mark. Hence A. P. Hill's comment, “Poor Kearny! he deserved a better death than this.” Redwood's own recollection, along with Haynes' account, left him well placed to produce this fine record of Kearny's last moment (Image 16):

After Ox Hill the Confederates crossed the Potomac and pressed on into Maryland. Redwood commemorated the occasion (Image 17):

By now the army had outrun its logistical supports. The troops were in a desperate state with worn out uniforms and shoes and little to eat. Lt. Healy recalled, “We heard with delight of the ‘plenty’ to be had in Maryland; judge our disappointment when about 2 o’clock at night, we were marched into a dank clover-field and the order came down the line, ‘Men, go into that corn-field and get your rations…’”19 Redwood produced two sympathetic portrayals of this moment, the smaller (Image 18) being a reworking of the larger(Image 19):

At this point, we are treated to a unique glimpse into the curious half-world of the Confederacy through a portrait (Image 20) of an otherwise unsung hero of the 55th. His name was ‘Bill Doin's’, a “lanky, cream-colored” [i.e. octoroon] sailor who found himself in the Confederacy as a result of the blockade and whose exploits as a forager and camp servant made him the best known man in the unit. Bill was possessed of “a scar which had drawn up the wing of the nose, given a cock to the eye and a twist to the corner of the mouth… and imparted… a sinister cast.” He rode a decrepit looking horse of remarkable stamina named ‘Stonewall’ upon which he ranged far and wide, never failing to return with food for the mess he served.

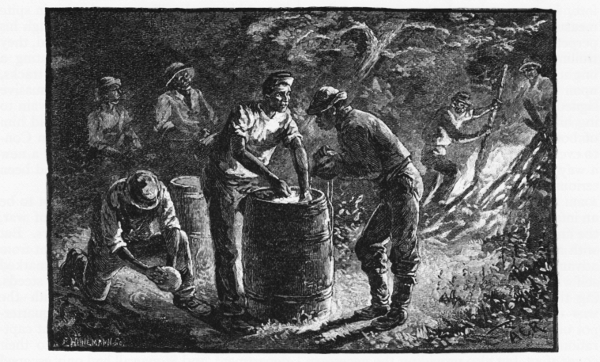

Even when not mistaking Bill for a member of the cavalry, the Q.M.D. left him in possession of his underestimated steed. Unfortunately, overcome by an excess of States Rights prejudice, ‘Stonewall’ refused to cross the Potomac and had to be left behind for good on September 5th 1862, but Bill marched on with the regiment and secured his place in its folk law less than two weeks later. On the night of September 18th, learning that the 55th was in line in a near starving condition, he took command of the other camp servants and, with nothing more than several barrels of flower, some canteens of water, a fence for firewood and an old hoe for an ‘oven’, succeeded in providing bread for 150 men, a feat commemorated in this wonderful picture (Image 2120 ):

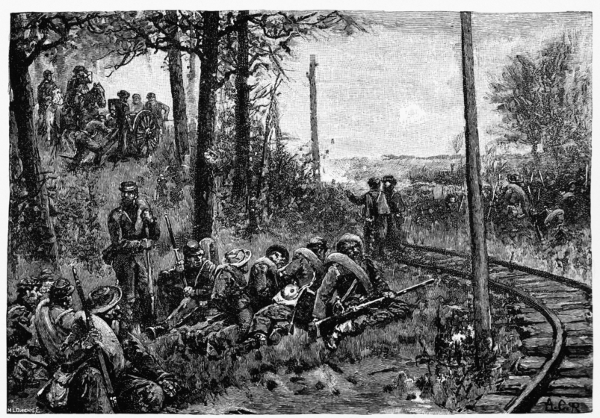

Redwood returned to the regiment at the end of September and witnessed the unit's improving strength and morale. He paid this tribute to its typical soldier, “There was no march so long or so toilsome, no occasion so serious, that it could quite dull the edge of his humor. The exceptionally hard service and many privations of his lot were one huge joke to him…”21 At the end of October the men of the 55th were engaged in tearing up sections of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (Image 2222) a task they enjoyed almost as much as teasing their beloved corps commander. His “dislike of notoriety was well known… and for this very reason the men… would yell like demons for the sake of, “making old Jack run.” ”

In December, Jackson's Corps marched to Fredericksburg and participated in the battle at that place on the 13th. The 55th was posted near Hamilton's Crossing on the extreme right along a two-foot-deep cut carrying the Richmond Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad. It was immediately in front of a rise known as Prospect Hill upon which the divisional artillery was stationed. All three are readily identifiable in Redwood's depiction of the scene (Image 2323):

Notes

1 Redwood's Compiled Service Record, U.S. National Archives, M-324, roll 968.

2 Miller's Photographic History, Vol. 8, pages 174 and 176.

3 Miller's Photographic History, Vol. 8, page 162.

4 Scribner's Monthly, Vol. XVIII, page 221.

5 The article was entitled “A Boy in Gray” and appeared in the September 1881 issue (Vol. XXII, pages 641 – 650).

6 When first published in Century Magazine in 1886, this picture was untitled. It acquired the title “Route Step” when republished in Battles and Leaders in 1888.

7 Century Magazine, Vol. 31, page 615.

8 Strictly speaking, this picture is untitled, but the editors of Century Magazine used it to introduce General Longstreet's article “Our March against Pope” and presumably felt any further description to be superfluous. The vignette of the two soldiers taking apples from the tree in the background suggests Redwood originally intended the picture to accompany his article “Jackson's Foot Cavalry at the Second Manassas”. (See note 7.)

9 Scribner's Monthly, Vol. XVIII, page 226.

10 The full title of this picture is, “Jackson's troops pillaging the Union depot of supplies at Manassas Junction”.

11 Century Magazine, Vol. 31, pages 617 – 618.

12 Century Magazine, Vol. 31, page 621; Redwood's Compiled Service Record, U.S. National Archives, M-324, roll 968.

13 Century Magazine, Vol. 31, page 615.

14 Redwood Collection (Box 1), Eleanor S. Brockenbrough Library, Museum of the Confederacy.

15 The biographical sketch of Mallory on pages 358-359 of the Memorial, Virginia Military Institute notes he had “a full dark beard and moustache”. The braiding on the officer's uniform is certainly commensurate with that of a field officer and Mallory was the only officer of that grade present with the 55th Va. at 2nd Manassas.

16 The caption attached to this picture by the editors of Century Magazine has been omitted here because it credits all of the troops shown as belonging to Starke's Louisiana Brigade and ignores the fact that the ones to the right of the picture are members of the 55th Va. coming to Starke's aid. The caption also states the action is taking place “near” the railroad cut whereas Redwood has depicted it occurring inside it. What looks at first glance to be a low earthwork is actually one side of the cut, behind which the stone throwers are sheltering. Lieutenant Healy's diagram, not published here, shows the cut carved into the side of a hill and Redwood has done his best to represent this by depicting the enemy lower down the hill than the Confederates. The viewer has to imagine himself standing on the track bed with the hill rising behind him. This stone throwing episode is referred to in O.R. Vol. 12, Part 2, pages 666 and 669.

17 Century Magazine, Vol. 31, p.620.

18 Battles and Leaders, Vol. 2, pages 537-538 notes.

19 Battles and Leaders, Vol. 2, page 620 notes.

20 Scribner's Monthly, Vol. XVIII, pages 561-563.

21 Scribner's Monthly, Vol. XVII, page 35.

22 Note the burning railroad ties and twisted rails in the bottom left hand corner of the picture.

23 The editors of Battles and Leaders attached a caption to this picture suggesting it represents troops of Hays's Louisiana Brigade, but the record shows that this sector was occupied by Redwood's unit and it was surely that fact that inspired him to paint it.